The Mongol Rally starts at Goodwood Motor Circuit in the U.K, passes through Mongolia, and ends in Ulan Ude in Russia. There are optional meet-ups and parties in the Czech Republic and Romania, but otherwise there is no set route.

While most teams tend to take the Northern route (through Northern Europe and Russia), or Southern route (through Turkey and the ‘Stans), previous teams have taken detours through China, the Arctic Circle and even Africa. Shane and I still have visions of taking the Trans-Siberian railway right across Russia one day, so decided to take the Southern route to see the highlights of Central Asia.

The only problem with the Southern route is that there is no obvious or easy way to cross from the Balcony of Europe into Central Asia. The options are:

- Drive from Georgia to Russia to Kazakhstan. This is, in fact, not a viable option since it would require a triple entry visa for Russia which are incredibly difficult (if not impossible) to get hold of, particularly if you are not on a business trip (and this is not a business trip).

- Drive through Iran to Turkmenistan. A significant number of teams have chosen this option, but it isn’t without its challenges. Visas for Iran are expensive and complex. To take a car into the country makes things even worse. You have to buy a $500 special passport for the car (a ‘carnet’), and British nationals also need to be accompanied by a guide (which requires even more money and paperwork). Shane and I have been to Iran before (and as a female traveller, I didn’t have a particularly positive experience), so we were keen to avoid the expense and the admin, and take a different route to Central Asia.

- Take a reliably unreliable ferry over the Caspian Sea. It is possible to take a cargo ship from Baku in Azerbaijan over the Caspian Sea to Turkmenbashi in Turkmenistan. The downside is that reports from previous Mongol Rally teams suggest this is anything but straightforward. From finding the port to buying a ticket, nothing is clear or simple. Everything costs a lot of money and takes a long time.

- Take an even more unreliable ferry from Baku to Aktou in Kazakhstan. As above, but even less clear, less frequent and more expensive.

The reliably unreliable ferry from Baku to Turkmenbashi seemed like the obvious, if not ideal, choice.

—-

On arriving in Baku, our first problem to solve was that neither Shane nor I had a visa for Turkmenistan. To apply for a five day transit visa (longer tourist visas are significantly harder to come by and require you to be accompanied by a guide through the country), you need a letter of invitation from the government of Turkmenistan. Despite applying for these letters in March, they arrived in July, just one day before the launch of the Mongol Rally, so we didn’t have time to apply for the visas before we left the U.K. Our options were to apply in Baku, or to get on the ferry without a visa and get it on arrival in Turkmenbashi.

In many ways, applying for the visa in Baku was a much riskier option. Our visa would only be valid for five days, and the unreliablility of the ferry meant that if we picked a date that was too soon, the visa could be used up before arriving in Turkmenistan, and that would be a big problem. However, we were repeatedly told that we would not be allowed to board the ferry to Turkmenistan without a valid visa (we wouldn’t be allowed to leave Azerbaijan without proof that we were authorized to enter Turkmenistan), so we set off for the Turkmenistan Embassy in Baku.

The opening hours of the Embassy were limited to Mondays and Fridays (9.30-12.00). Those are the only opening times. We arrived in Baku on a Wednesday night, so after a day of sight seeing on Thursday we were at the Embassy bright and early on Friday morning. After a long wait and some frustrating queue jumping (we saw some locals bribing the guard at the Embassy to reach the front of the line), we were told that the Embassy had no electricity, so could not process any visa applications. We would need to get the visa on arrival in Turkmenbashi or come back on Monday.

As Monday was three days away, we thought we might as well try to board the ferry without the visa. If it didn’t work, we could return to the Embassy and try again. There was a boat in the port, which was apparently sailing to Turkmenbashi that day, so we made our way over there to try and buy a ticket. We met Viktorya at the ticket office. She seemed to be in charge, and she (somewhat aggressively) directed us to sit in a waiting room. She would let us know when she had some information about whether we could buy a ticket.

When she returned, it was with bad news. She didn’t have enough cargo to justify the sailing. The boat was too empty. She said we should come back tomorrow and try again.

—-

Along with several other Mongol Rally teams, we arrived at the port around 9am the next day. Viktorya hadn’t arrived yet, but we found the waiting room full of other people who were also eager to get on a boat. When she arrived, Charlie (from team Genghis Kart) went to speak to her and there was more bad news: the ferry was now too full. There wasn’t enough space for everyone who wanted a ticket. We were told to wait to see whether there would be space for us.

So we waited. And waited. And waited a bit more. Eventually something seemed to change, and we noticed local people queuing up at the ticket office and handing over money. It seemed that it was possible to buy tickets now after all. We joined the queue. It was a long process (more local queue jumping occurred) but eventually the first Mongol Rally team in the queue managed to buy tickets, and all was looking well.

But then there was a sudden change in fortune. Having been told there would be enough space for all the Mongol rally teams, there were now only four more spaces for passengers on the ferry. Charlie from Genghis Kart was next in the queue and had been waiting since Thursday night (it was now Saturday), so it made sense for his team of three to go with Jamie (who was a team of one).

Except then Viktorya had another idea. There was apparently plenty of space for cars, just not for passengers. She suggested that four car drivers board the ferry with their vehicles, and that the remaining passengers take a speedy passenger ferry, which would leave the next day, and should bring us all to Turkmenbashi at the same time. There were four drivers from four teams in the queue: Charlie (from team Genghis Cart) Lucas (from team Silicon Rally) Roland (from team The Flying Dutchmen) and me, and all agreed that this seemed to make sense, as it would get the maximum number of people to Turkmenistan as soon as possible. Each of the drivers bought their tickets, visited a separate office to pay the extra $12 fee for using the ramp on to the boat (yes, really), and started to sort out the cars to make sure passengers had what they needed for the day and for the ferry crossing.

While my rational brain agreed with Viktorya’s plan, the idea of getting on the ferry and going all the way to Turkmenistan without Shane wasn’t appealing. I would miss him, and I started to worry about what could go wrong. Where and when exactly would the passenger ferry go? Where would we meet in Turkmenbashi? What if one of us got stuck on one side or the other? Out of all the parts of the trip where we could be split up, this seemed like the worst part to separate. It suddenly felt like a terrible idea, and I felt quite panicked.

All of a sudden, Viktorya realized she had one extra space for a passenger on the ferry. After establishing it was just for a passenger (now there seemed to be a space for a passenger but no more space for cars…), the other teams suggested Shane buy the ticket, as we were the only team of two. It was our lucky day. Little did I know at this point just how lucky.

—

After a few hours of hanging around waiting for the ferry to load and passing through customs and passport control, we were welcomed on board the boat. We were led to a room that turned out to be the main social / dining spot, where cabins were being distributed. Lots of angry shouting from other passengers revealed there was another problem – there were not enough rooms for everyone on board.

The Mongol Rally teams were the last to be given cabins, and they were quite obviously the worst ones on the boat, and perhaps weren’t meant to be used at all. They were a floor below every other room (next to the engine) and consisted of two rooms with six bunk beds and one toilet for 12 of us. But, at least there were bunk beds. And an all-important toilet. It could have been worse.

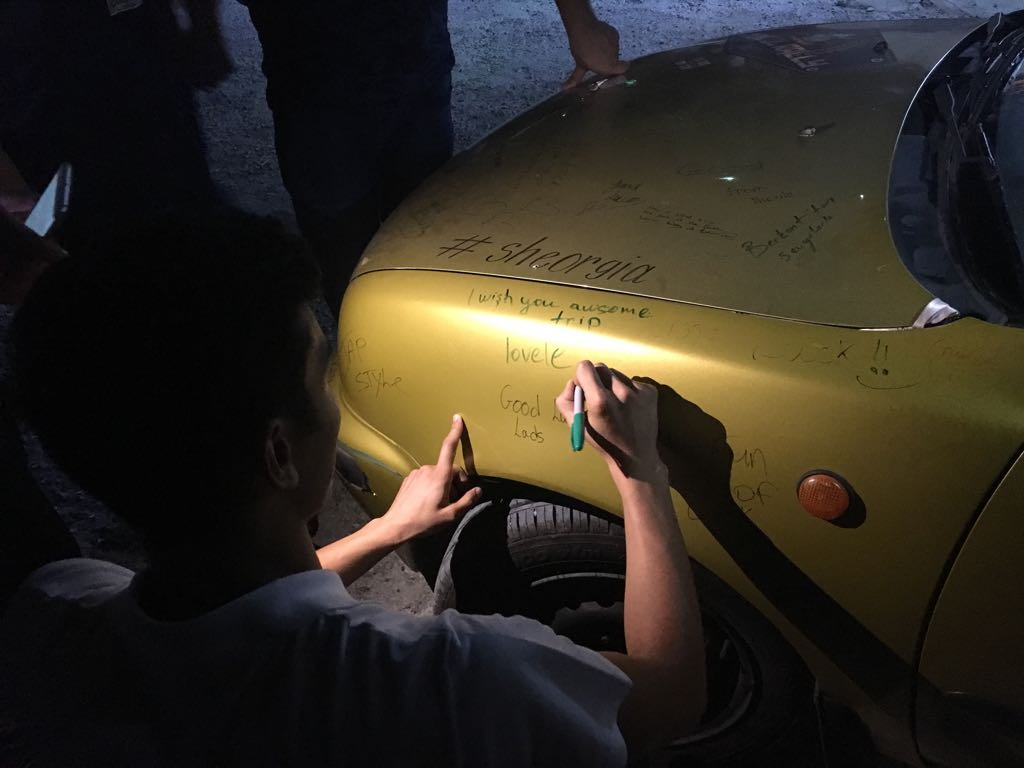

The boat journey was hot and not always comfortable, but it was an experience. We made friends with the locals (and were invited to share their dubious cheese, tomatoes, soft drinks and vodka), watched a lot of Russian films, got invited to explore the bridge and relaxed watching the sunset over the Caspian sea.

Waving goodbye to Baku and setting sail on the Caspian Sea

All was going well, and we reached Turkmenbashi in around 18 hours as promised. However, we couldn’t get off the boat yet. The port was congested, so we had to wait on the boat a little way out in the water. For another 22 hours. This meant our 18-hour boat crossing took 40 hours. We were happy enough on the boat (and had three free meals a day for the whole time on board), but had we been in a rush to get somewhere, this might have been a bit annoying.

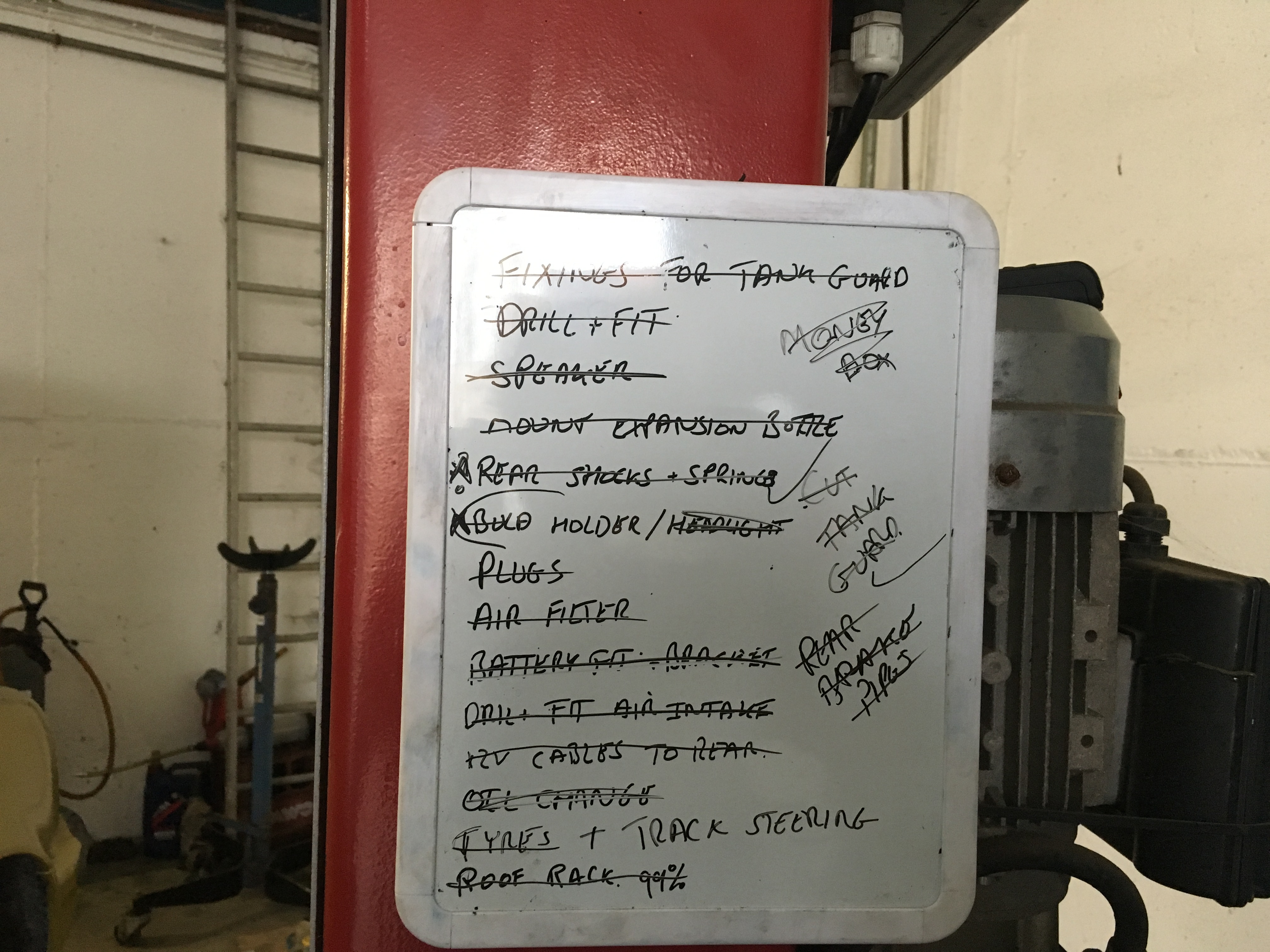

Shane getting to work

Friendly little boat in Baku helping us out of the port

View of the Caspian Sea from our “cabin”

Martha enjoying her time on the boat with other rally cars

Passing the time on the 40 hour crossing

Sunset on board as we approached Turkmenbashi

Chilling out on the boat

When we finally docked in Turkmenbashi, we needed to give our passports to the officials on board. I sent Shane to get our letters of invitation to prove we were authorized to enter Turkmenistan (as we were yet to get hold of the visa) and followed the official into an office in a part of the boat we hadn’t yet visited. Then another man told me to follow him, and led me through some windy corridors around the ship. I started to feel a little anxious. I wasn’t sure where he was leading me or what this was all about. I was on my own, and no one (including Shane) knew where I was. The man opened a door and told me to follow him into a room.

A wave of cool air washed over me. This room was air conditioned (unlike the rest of the boat), and there were plates of cherries, sunflower seeds and cold drinks on the table. “I am the captain”, the man said, and invited me to sit down and enjoy a cold drink, a bite to eat and some Russian films. We had been communicating and watching Russian films together for a while, when I could hear Shane outside calling for me, so I shouted back and he joined us for some more cherries and a Russian soap opera.

After two or three hours with the captain, it was time to leave our air conditioned oasis and get off the boat. As we reached land and our phones picked up a signal, we had some bad news. The promised ‘passenger ferry’ hadn’t materialized. The passengers from the three teams with us were still in Baku. They weren’t getting on a boat that day, and couldn’t be certain they would get on one the next day. Despite our delayed ferry crossing, they wouldn’t be able to catch up. We only had a five-day visa to get across Turkmenistan, and the passengers were at least two days behind.

—

The problem became even clearer as we started the process of entering Turkmenistan. There was no option for the teams to stay the other side of the border and delay their visas starting. There was no flexibility on the visa dates. In fact, there was no flexibility on anything, and we wouldn’t even be allowed to stay in Turkmenbashi for a day or two to give them the chance to catch up. Shane and I were the only ones lucky enough to be together, and we planned to stick with the drivers from the three split teams for as long as we could.

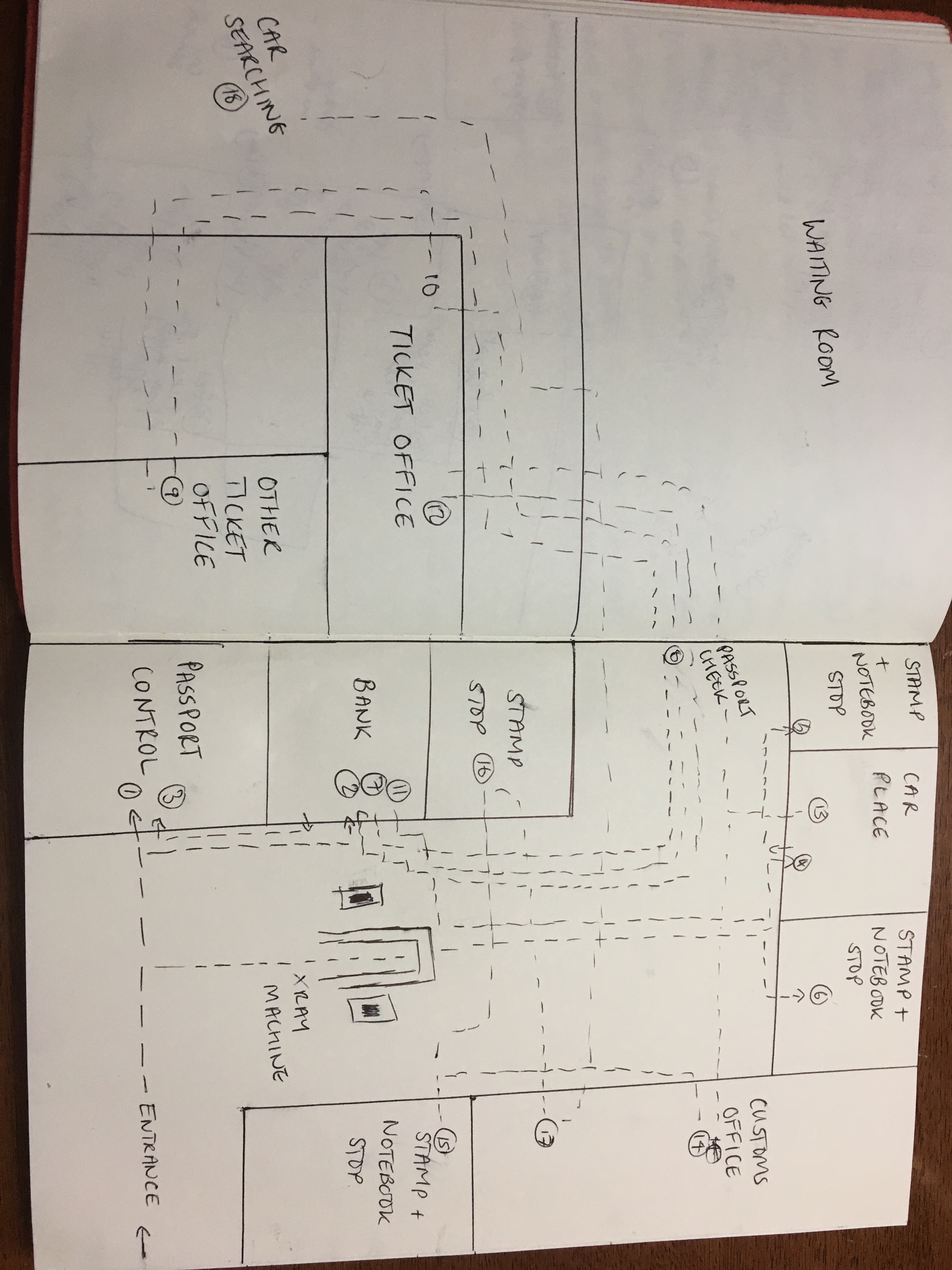

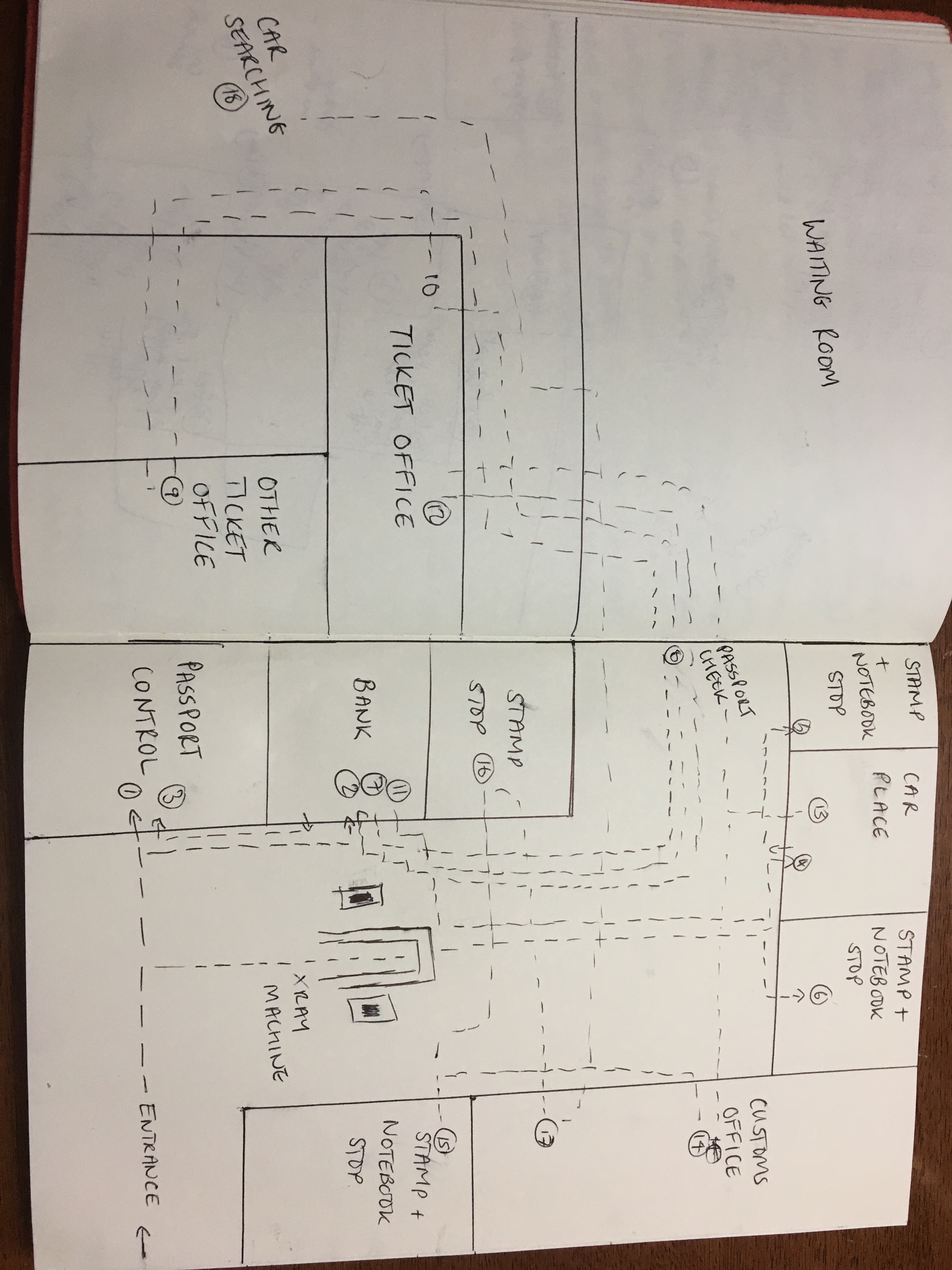

Entering Turkmenistan was bureaucracy on a whole new level. I have never experienced anything like it, and I don’t know whether anyone reading this will even believe it, but this is the condensed version of exactly what happened:

Step 1: Apply for visa. We had to give in our passports, and a detailed itinerary of where we would be on which dates. Except that it turned out we had no choice in this. We had to follow a set itinerary that the Turkmenistan government had already been decided for us. (Luckily this fit with our planned itinerary). We could not stay in Turkmenbashi. We had to go straight to Ashgabat THAT DAY (even though it was an eight hour drive away and we would probably get there in the middle of the night, given the length of time the immigration process took). And so on.

Step 2: Pay for visa. This had to be done at the bank, rather than at the passport office. For UK citizens, this was $85, plus a $14 “entrance fee” and a $2 “extra charge”. For Irish citizens, this was a bit cheaper ($55, plus $14, plus $2). This could only be paid in US dollars.

Step 3: Back to passport control. Have fingerprints taken, photos taken, reconfirm all details in the passport and all car details.

Step 4: Visit an office on the other side of the building (this involved first going through an X-ray machine) to complete some paperwork for the car. All details about me, the car, the route we were taking and various other bits and pieces were written into a big notebook. Then a form was filled in with a bill on it, and given to me. I was told I needed to take it to two additional offices, and then to the bank to pay the bill.

Step 5: Take the same paperwork to a man in the office next door. He filled out all the information into another big notebook, and gave me some kind of stamp.

Step 6: As above, but in another office two doors down.

Step 7: Try to pay the money I owed for the car at the bank (about $170 for insurance, fuel compensation, tax and extras). Unfortunately the lady at the bank told me there were some extra steps involved. I had to first go and get a ticket, then go to the ticket office, and then come back to the bank.

Step 8: Visit an office behind the ticket office (this involved leaving the area, so I had to show my passport).

Step 9: Collect a ticket from the office behind the ticket office.

Step 10: Take the ticket to the ticket office (all the details were copied out into another notebook and another piece of paper was given to me).

Step 11: Back to the bank where I was finally able to pay (in US dollars only), get a receipt and some more bits of paper.

Step 12: Back to the ticket office where I had to pay for something else (in the local currency, Turkmenistan Manat, only – challenging when you can’t get any outside of Turkmenistan and there is no ATM or money changer at the border), get a receipt and more bits of paper.

Step 13: Back to the original car office with the receipts to collect some more paperwork.

Step 14: Go to the customs office, fill in a customs declaration form, and watch as my details are written down in another notebook, and another form is filled out and more paperwork provided.

Step 15: Get my new bit of paperwork (the customs form) stamped. This involved yet another note taking exercise and questions about me and the car.

Step 16: Get another stamp for the customs form.

Step 17: Take the stamped form back to the customs office. Finally given the all clear to go.

Step 18: It turned out we were not quite clear to go – it was now time for a thorough car search. I had to find and identify every sort of medicine we had, and they went through various bags. They even read my books. We got off lightly compared to the other Mongol Rally cars though.

Finally, after at least six hours of moving from office to office, handing over wads of cash and seeing my name and details written in more notebooks than I could ever imagine, we were free to go. Well, as free as you can be when you have been clearly told that you must drive eight hours to Ashgabat, and it’s already 6.30pm.

Crossing the Caspian Sea was expensive and difficult, but it was an experience, and it was worth it to see Turkmenistan and to make it into Central Asia.

Map of the process to enter Turkmenistan

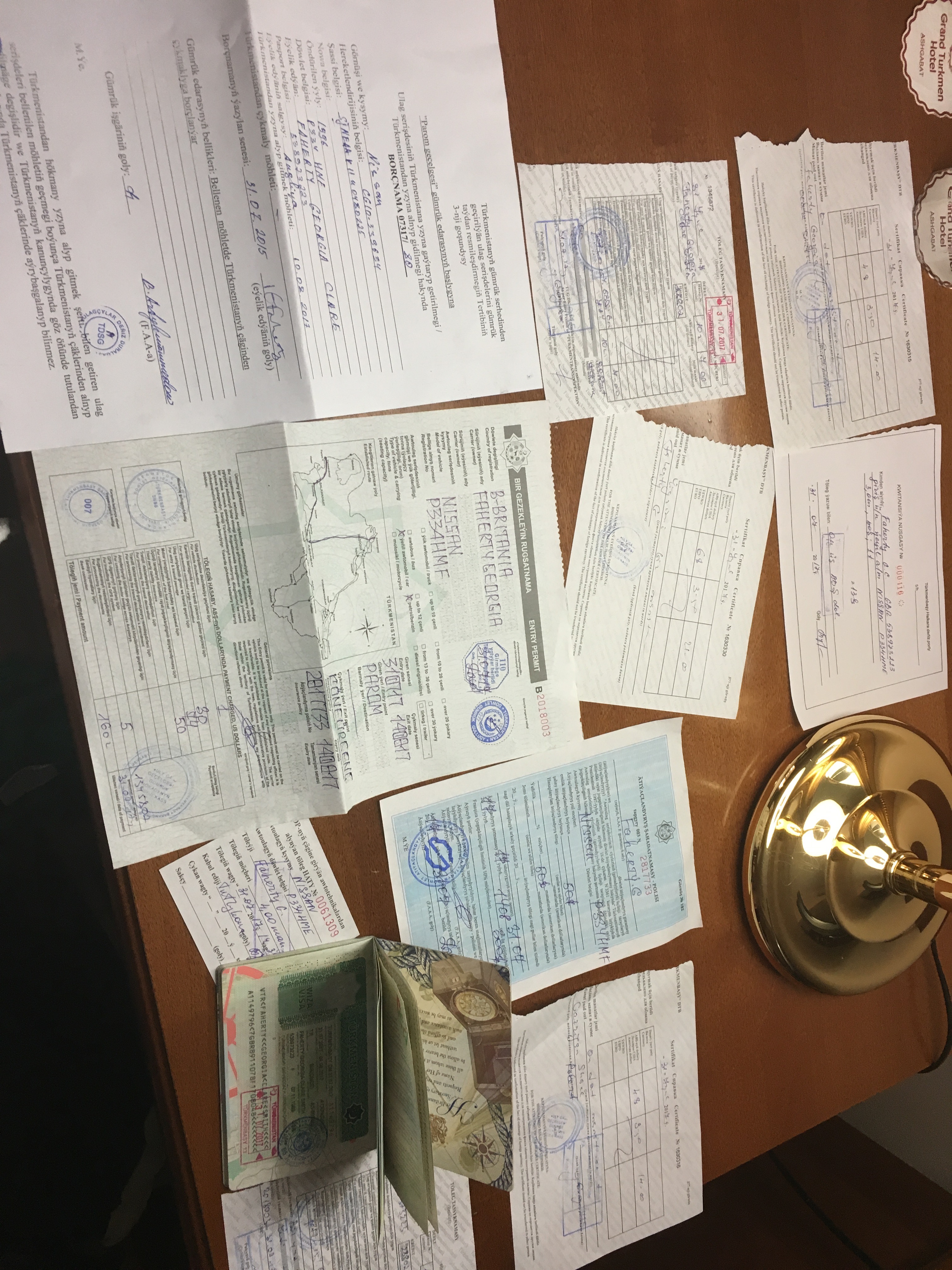

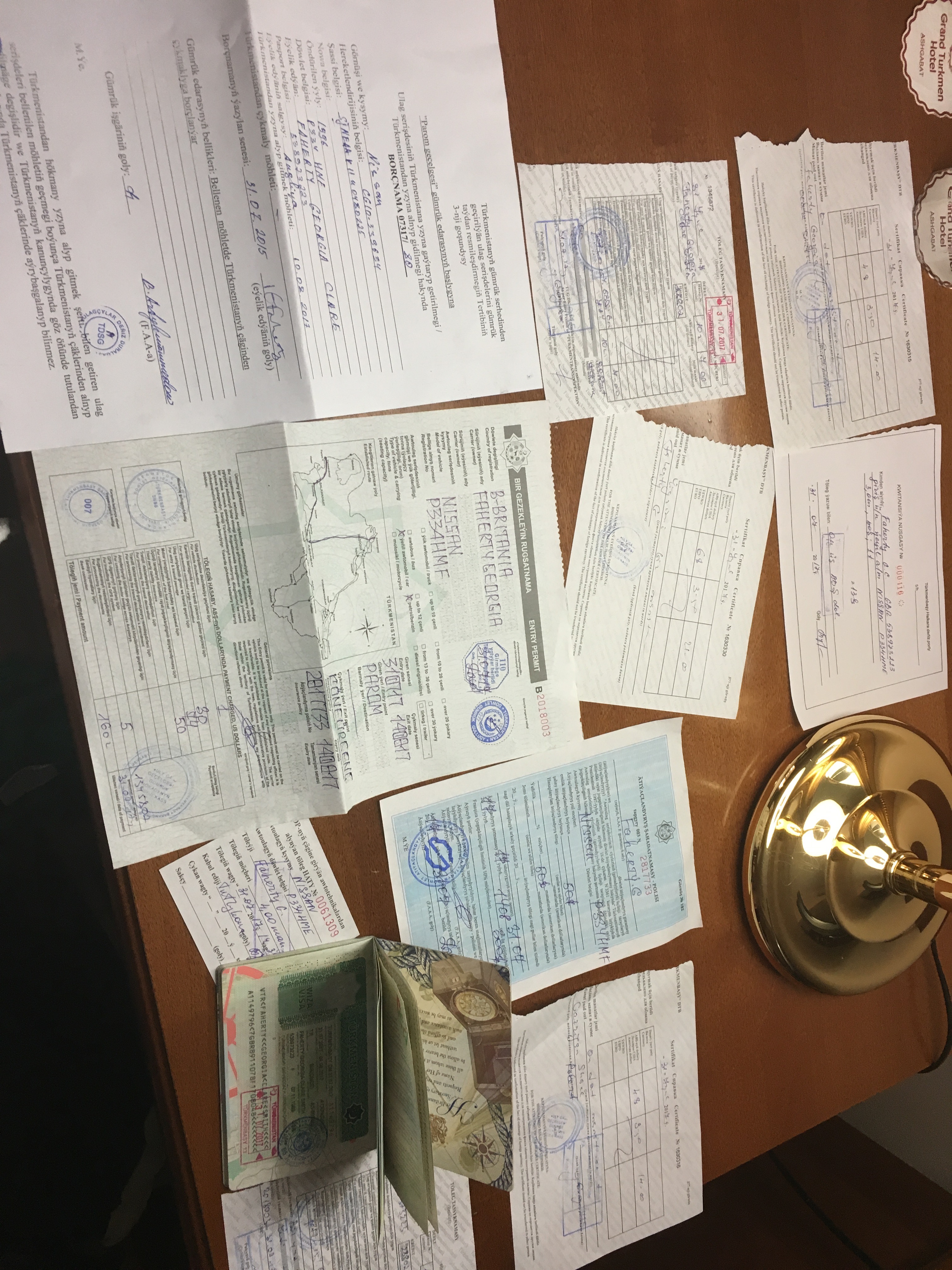

Some of the paperwork and stamps collected

Crossing the Caspian Sea:

Total time: Five days (4 hours attempting to get a visa, 3 hours waiting for the ferry on day one, 12 hours waiting for the ferry on day two, 40 hours on the ferry, 3 hours unloading time, 6 hours entering Turkmenistan).

Total cost: $634 ($340 for ferry tickets for Georgia, Shane and Martha, $12 fee for using the ramp to board the ferry, $140 for Turkmenistan visas, $28 for entrance fee to Turkmenistan, $4 for extras, $30 for Martha’s entry and transit passage, $74 for fuel consumption – fuel is ridiculously cheap here, so tourists have to pay an extra charge for every mile they drive – $5 for processing the documents, 4 Turkmenistan Manat (about $1) for something which remains unclear).

Pieces of paper and stamps collected: Too many to count.