Turkmenistan wins the prize for being the strangest country we have ever been to. It is also one of the most secretive countries, and as you may remember from our last post, it isn’t exactly easy to visit.

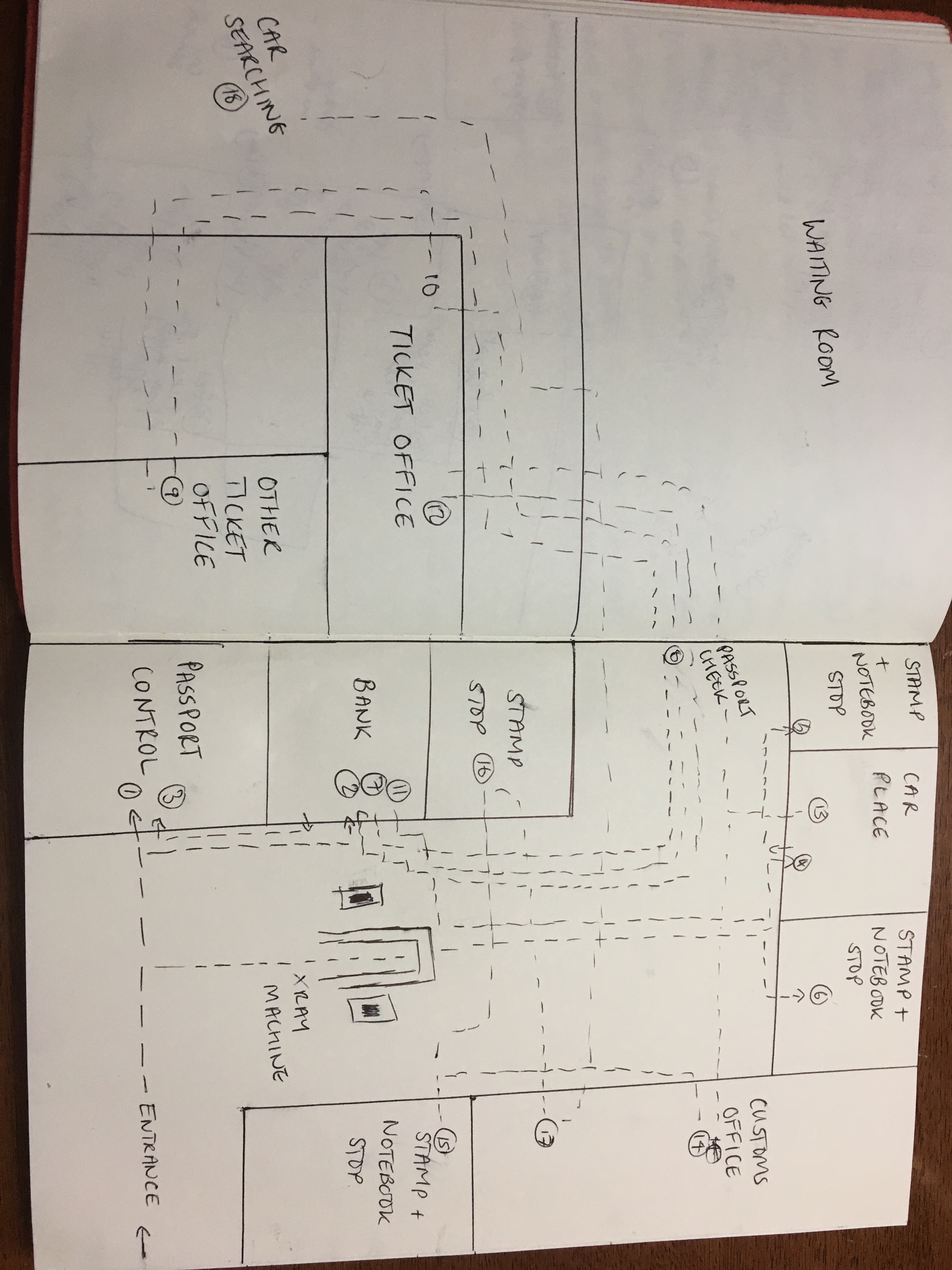

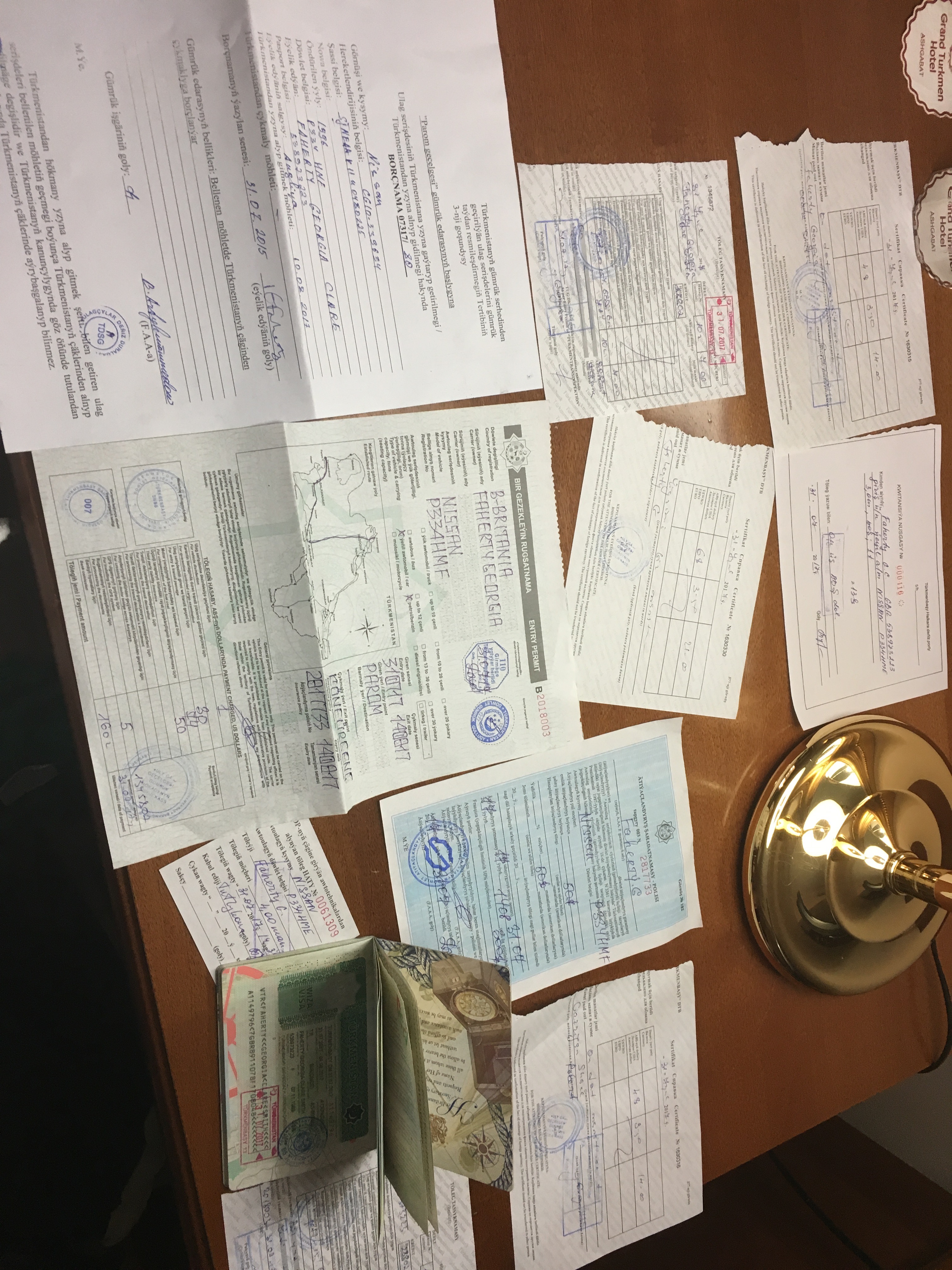

By the time we had left the boat, collected all the stamps, filled in all the forms and paid all the fees required to enter Turkmenistan, it was 6.30pm. The border guards were adamant that tonight we must drive to Ashgabat (the capital), which was at least seven hours away. This wasn’t ideal - we were worried about driving so late at night, and there were a lot of unknowns. We didn’t know what the condition of the roads would be like, we didn’t want to hit any camels, didn’t know whether it was safe, and there was rumoured to be a curfew in Ashgabat which meant you couldn’t be outside (or driving) after 10 or 11pm in the city.

But it was clear there was no choice. We had to get moving, and we wanted to make the most of the available daylight. Thankfully we were with Charlie, Lucas and Roland – the drivers from the teams that had been split up – and we tackled the roads together in convoy. As we drove off, the border guards cheerfully reminded us not to worry: “You will be very safe here. Immigration know exactly where you will be at all times”. Reassurance came with a side order of threat… we had definitely entered a dictatorship now.

If our first impressions of Turkmenistan were that it is an inflexible maze of bureaucracy, filled with stamps, repetitive notebooks and ridiculous charges, our second impressions were that it was one big desert. On the road to Ashgabat we saw a lot of sand, some camels, a few small settlements, and some more sand. Once the sun went down, we found ourselves in a giant sand cloud, which was less than ideal and meant we had slow down. It didn’t help that despite being on a highway, there seemed to be no rules about which side of the road to drive on. Cars hurtled towards us as breakneck speeds, but also approached us from behind. At one point, Lucas (team Silicon Rally), pulled over. “Are we driving on the right side of the road?”, he asked. It remained unclear.

Lucas from team Silicon Rally storming through the Turkmenistan desert

We finally made it to Ashgabat at 4.00am, after nearly 10 hours of driving. Ashgabat looked like a bright, white city, lit up like a Christmas tree, in the middle of the desert. The Lonely Planet had warned us that there was “no budget accommodation in Ashgabat”, and this seemed to prove true. We had identified one “mid-range” hotel, but it was full. Across the road stood the five star Grand Turkmen Hotel, complete with secure parking, air conditioning, swimming pool, breakfast and wifi (well, “wifi” – it didn’t really work, and all social media is banned in Turkmenistan anyway). They had rooms, and although it wasn’t cheap, the idea of a bed for the night (not to mention a comfy bed with all the available amenities) was appealing enough for us all to blow our accommodation budgets and check in.

---

A day of sleeping and sight seeing followed. As we wandered around Ashgabat, it seemed no expense had been spared in making the city look fantastic. Every building was massive, grand, white (with a hint of gold), spotlessly clean and accompanied by a varying number of fountains. Huge monuments and gold statues littered the city. There were giant squares and parks everywhere (many of which were called “independence square”, or “independence park”, or another similar variation), filled with symmetrical fountains and plants. There were also a considerable number of gold statues, many of which were of the previous President (apparently he had given in to the “huge pubic demand” for thousands of statues of himself. What a good man he must have been.) A stomach turning amount of water was used to keep the city green and keep the thousands of fountains going in the middle of the desert. The city was also spotlessly clean, and you could be fined for having a dirty car (luckily no one spotted Martha, who wasn’t exactly sparkling after driving through a desert sand storm).

Horse statue (and many fountains) in Ashgabat

Symmetrical fountains, tall white buildings and suspiciously green plants in Ashgabat

Martha visits the Monument of Neutrality, Ashgabat

Ashgabat by night

The weirdest thing about the city was that despite its grandeur and its obvious desire to impress, there was no one there. There was a police officer on every corner, and no shortage of cleaners keeping the place immaculate, but there was no one actually in the parks or looking at the fountains or anywhere at all. We were also told we couldn’t take photos of most things, and as we tried to walk across the city were met by Police telling us we couldn’t go any further. It made us question why the government had spent so much time and money making Ashgabat so impressive. Not to impress tourists or foreigners (after all, there were none apart from us – Turkmenistan isn’t exactly an easy place to visit), not to impress or satisfy its own people (again, there were none), and not to impress anyone far away or make Turkmenistan seem like a great country (we couldn’t even take a photograph). Was this all just one massive ego trip for the previous President? It was very surreal, a little eerie, but undoubtedly extraordinary.

---

As we only had five days to get through Turkmenistan, we couldn’t hang about in Ashgabat for too long. Next stop on the route was a crater of burning gas in the middle of the desert, otherwise known as the gates of hell.

At this point we said goodbye to the drivers from the split teams – their passengers were now on their way to Ashgabat, and they would all come to the gas crater later in the evening or the following day. We travelled up the road to hell with another team from Sweden, who had two cars with four people in each. They were a very friendly team, and they gave us one of their walkie-talkies so we could communicate on the way.

We arrived at the track to the crater with very few issues, apart from having to stop a few times to avoid camels crossing the road. When we did reach the track, we were faced with an interesting sandy hill, and a number of locals in jeeps – some of whom told us we would never make it to the crater in our rubbish cars, and some of whom said we could get up the hill if we approached it from a long way back and went really, really fast.

Martha and some camels on the way to Darvaza (hell)

More camels in the desert

One of the cars from the Swedish team made a first attempt up the hill, while Shane changed the tyres on Martha (we had brought special mud/sand/snow tyres with us which we thought might give her a bit more grip). The first car made it part-way up the hill, but got stuck in the sand. After a bit of pushing, the car was free. It went back down the hill and did better second time. The second car made it up the hill with no problems, but Martha wasn’t so lucky. Shane had four attempts, and on the fourth, all eight people from the Swedish team ran down to push Martha the last few yards. With their help, she made it up.

But over the hill, more sand was waiting, and every single car (including others that arrived, and, of course, Martha) got stuck in the sand. The locals and their jeeps were back, offering different services for different exhorbitant prices (they could drive our cars to the crater for us, for $150 per car!). While Martha could reverse back out of the sand, it was clear she wasn’t going to make it all the way to the crater (at least not any time soon, or without a lot of pushing). Most of the other cars were so stuck that they couldn’t even get back without a lot of help. We were going to need to do some sort of deal with the locals if we wanted to see the gates of hell.

And so, the negotiations began. It wasn’t easy. With so many teams now completely stuck, we had limited bargaining power. The sun had set, and darkness was creeping in, along with various insects. The desert was home to scorpions and spiders and snakes, and we wanted to get out of it and see the burning hole. Eventually, we agreed on a price of $10 per person plus two packets of cigarettes for transport to and from the crater, and to help get the stuck cars un-stuck in the morning.

A long, bumpy ride followed, but we made it to the gates of hell! The burning gas crater was huge, spectacular and hot, and did look like it could be the entrance to hell as the desert seemed to just fall away around it.

The big fiery hole (gas crater) at Darvaza - the gates of hell

Shane and I at the entrance to hell

We camped right beside Martha that night, and after another negotiation in the morning (the locals wanted more money and more cigarettes for moving the stuck cars, so Shane suggested they provide us with a receipt which we show the military police, and suddenly they were happy enough with what they already had), we were back down and ready to drive the 250km or so to the border and enter Uzbekistan.

---

We were expecting a three to four hour drive, and to arrive at the Uzbekistan border by around 11am, giving us plenty of time to cross over (and deal with the inevitable border bureaucracy) and a leisurely evening on the other side.

As we drove off, we waved goodbye to our new friends from the Swedish team (they had been given a different prescribed route when they entered Turkmenistan, and had even been given a black box which tracked their every movement), and started on our journey.

This didn’t go exactly as planned. The start of the road was bad – it was bumpy and littered with pot holes. Then it got worse. And worse. Eventually we found ourselves on a gravel track. Shane expertly avoided the bumps, but it was very slow going. We finally reached the border at 4pm, after around 8 hours of driving, and found it strangely empty: it was almost closed.

Struggling to avoid potholes on the road from hell

Luckily we were just in time, and as the border police undoubtedly wanted to get home for the day, the process wasn’t too arduous. We were across by 6pm, and felt a newfound sense of freedom as we entered Uzbekistan: our route was no longer fixed, and our visas were valid for 30 days. While our experience of Turkmenistan had been interesting and unique, it had also felt a touch oppressive and difficult. While the surface of Turkmenistan glittered and sparkled, the emptiness, the crazy bureaucracy and the thousands of police officers and soldiers hinted that something underneath wasn’t right.