We’ve spent one weird and wonderful week in the biggest, busiest mega-city in the world. Rather than give a detailed blow-by-blow account of how we spent every minute of every day, we thought we’d change it up a bit and summarise ten of our favourite (or most interesting) Tokyo experiences.

- Commuter hell: the Tokyo rush hour challenge

It was about one o’clock in the morning when our plane touched down at Tokyo’s Haneda airport. This wasn’t a great time to arrive, as public transport shuts down at midnight in Tokyo. We chose to attempt to sleep in the airport rather than pay for an expensive taxi, which had an interesting unexpected consequence: we got up in the morning, and hit rush hour on Tokyo’s transport network.

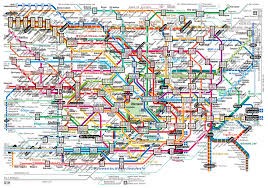

Rush hour in Tokyo is a bit like rush hour in London, only there are a lot more people involved. Tokyo is the most populated city in the world, and every day about 40 million people travel on the rail network. The Japanese even have a term for the daily rush hour challenge: “tsukin jigoku”, which means “commuter hell”. When we changed trains at the city centre, Shane and I stood back for a while just to watch rush hour people traffic. It was like watching schools of fish in the sea. Everyone knew where they were going; it was as if they were caught up in a stream, and different streams moved in the same direction continuously. It wasn’t overly stressful or frantic, but you had to slot into your place in the stream, which was something Shane and I obviously failed to do as we bumbled around with our big bags trying to decipher the Japanese signs and work out where to go next.

We found our way, and waited on the platform for our train. As it approached, we noticed it looked rather full. “We’ll never get on there with our bags”, said Shane. “Well we don’t have much choice”, I replied. The train was full, but the next train would be full too. We managed to squeeze on and survived our journey, sandwiched between people like sardines.

Tokyo’s rail and subway network

- Harajuku’s owl cafe

Tokyo is full of animal cafes: places where you can get a drink, have a snack and chill out with a cat, goat or even a hedgehog. While I loved the idea of a hedgehog cafe, I also thought it might prove a little prickly, and I was quickly captured by a softer alternative – an owl cafe. The owl cafe in Harajuku sounded great. A place where you could sit, have a drink, and stroke an owl at the same time. Owl cafes are even advertised as “healing” places, as stroking an owl can apparently reduce stress.

Sadly, the reality of the owl cafe was a little different. We arrived at our appointed time, were given a drink, and then waited for our allotted 35 minutes of owl time. “Cafe time” and “owl time” had to be separated for hygiene reasons, so it was more like having a quick drink and then heading to a petting zoo than the holistic “owl cafe” experience I had imagined.

Next we read the owl cafe warning card, which included warnings such as “don’t take the smaller owls near the bigger owls, because the bigger owls will eat them” (comforting), and “watch out for owl excrement” (lovely). When it was time, we proceeded outside onto a little balcony area of the cafe, where about 10 owls were sat waiting for us. It then dawned on me that 1) the owls looked sad as they sat chained to their perches and stared out of the window wishing for freedom, 2) owls are nocturnal animals, so keeping them awake during the day for tourists to stroke them probably wasn’t ideal, and 3) the space they lived in was probably too small for them to be happy.

I half heartedly stroked an owl, and then witnessed a very large owl jump (almost hitting me), as if it were trying to escape. That was the end of our time in the owl cafe.

One sad looking owl

Another sad looking owl

- The robot restaurant

Another day, another disappointment. As a robot enthusiast, I couldn’t miss Tokyo’s robot restaurant. Despite the fact it was obviously super-touristy and overpriced, and despite Shane’s protestations that “they won’t be real robots” (I disagreed, it was called the ROBOT restaurant after all!), I just had to visit the robot restaurant.

Sure enough, it wasn’t really a restaurant, and there were no robots. However, there was some very interesting (completely bizarre) entertainment, complete with glow sticks, flashing lights, bright colours, loud music and strange costumes. We might not have seen real robots, but we did see a giant fish, a giant chicken, the full cast of the show singing the YMCA, and much, much more. It wasn’t what I was hoping for, but it was a once-in-a-lifetime (I am never doing it again), out of this world, surreal experience.

When you go to a robot restaurant… and a giant fish turns up

Shane enjoying the psychadelic robot restaurant atmosphere

- Tsukiji Fish market

Tokyo is home to the biggest fish market in the world. It’s a wholesale market so tourists aren’t overly welcome. In fact, we weren’t allowed inside until 10am, and even then our movements were closely watched and we were banned from taking photographs… although I did manage the odd sneaky fish photo. We saw quite a few interesting sights at the fish market, such as packaged “snacks”, including an “eel bone snack” (I don’t think eels have bones, but never mind), a “dried kelp snack”, a tiny-octopus-on-a-stick, and more. We also saw some fish getting chopped up while still alive (there was a lot of wriggling and flapping about), and various other tanks with live fish and squid. It seems the system is that you select your fish while it’s still alive, and then it is chopped up and given to you in a bag!

We would have liked to get to the fish market in time for the tuna auction, which takes place every morning at 3am, but only a limited number of tourists are allowed to watch, and 3am was a little too early for us!

Tsukiji fish market

Eel bone snack

Octopus on a stick

Fishes at the fish market

- Weird museums

So little time, so many weird museums. One of Tokyo’s finest museums has to be the very small but beautifully formed parasite museum, where you can look under a microscope at tiny parasites and learn about how parasites get into your body and what they can do. We learnt about the history of parasites in Japan (eating sushi = parasites for life) and even saw an 8.8m long tape worm!

Parasites

8.8m long tape worm

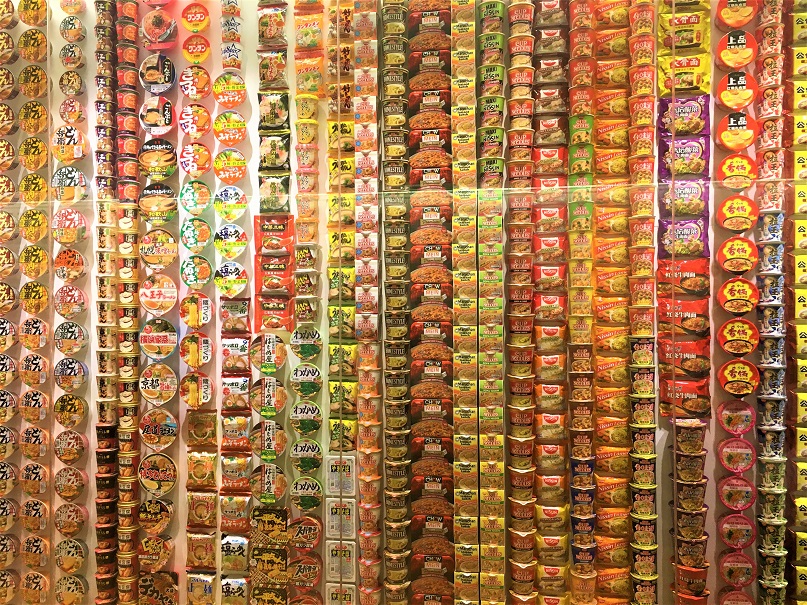

Another highlight was the Cup Noodles museum in Yokohama. The Cup Noodles museum contains five floors of exhibits about Cup Noodles. In the Cup Noodles museum you can explore a replica of the house where cup noodles were first invented, view noodle-related artwork, make your own cup noodles and (if you are under 10 years old), pretend to be a noodle in the noodle park. While I could barely contain my disappointment about being too old to play in the noodle park, I had a lovely time making my own cup noodles, although I may have chosen some slightly odd flavour combinations. I visited the Cup Noodles museum with my parents, and on the way out asked my Mum whether the whole thing was for real, or whether it was a bit of a joke. “Absolutely for real”, she replied, “it’s like the Japanese version of Cadbury World.”

Making our very own cup noodles

Cup noodle related artwork

Lots of cup noodles

- Senso-ji temple

Senso-ji temple is Tokyo’s oldest temple, founded in 645 AD. It is an Ancient Buddhist temple and is the most widely visited spiritual site in the world. It is located right in the heart of the city, surrounded by imposing gates, touristy shops and is next to a five storey pagoda (the Asakusa shrine).

On our visit to Senso-ji temple we explored the nooks and crannies of the temple grounds, marvelling at the big golden buddha statues. The main shop-lined street leading up to the main building of the temple was hectic, with worshippers and tourists alike jostling to buy their souvenirs and reach the temple, but beyond that it was a calm and quiet place complete with a contemplative garden. Within the temple itself it was also possible to consult with the oracle (for the small price of 100 yen – about 75p). We’ve seen some fantastic temples already in South Korea, and although this temple wasn’t as aesthetically impressive, it was more original and felt more like a place of spiritual significance than a big tourist attraction.

Senso-ji temple

Senso-ji temple

- Shibuya crossing

Shibuya crossing is a massive pedestrian crossing outside Shibuya station in central Tokyo. Pedestrians can cross in about twelve different directions, and it is a great opportunity to watch a sea of people moving quickly and seamlessly through Tokyo without being caught in the middle of the people-crush. We visited the crossing at about 2pm on a weekday – far from rush hour, but the crossing was still busy. We spent a good hour or two here just people watching from different angles and trying to get a good photo. Check out the link to our instagram page below for a quick video of the crossing in progress:

https://www.instagram.com/p/BZiYFC8A13-/?hl=en&taken-by=shaneandgeorgia

Shibuya crossing

- Staying at a capsule hotel

On our first night in Tokyo we stayed in a capsule hotel. This is something I’ve always wanted to do (Shane was less keen), but we both enjoyed the experience. In fact, it was probably the nicest place we’ve stayed so far, although that might say more about the standard of our accommodation to date than anything else.

We stayed at Nine Hours North – a trendy, modern capsule hotel in Shinjuku, and one of the few capsule hotels that allows both men and women to stay the night (most capsule hotels are male only). The capsule hotel had a clean, white, minimalist design. Check-in was simple and efficient, and we were given a locker key, a capsule number and a bag with free pyjamas, slippers and towels. There were separate floors for men and women and one bare common room area with charging points, desks and chairs. There were also clean and fairly luxuourious washroom areas for men and women, with excellent toilet and shower facilities. The toilets were particularly exciting, as they had a number of different buttons for different functions, although it wasn’t always easy to work out what was what. In Shane’s words, you needed a degree to use the toilets.

The capsules themselves were comfortable and more spacious than expected. There were over 50 capsules in each room, but my little pod was surprisingly quiet and felt very private once I pulled down the blind separating me from the outside world. I also had a light and charging point in my capsule. Both Shane and I enjoyed an excellent night’s sleep inside.

Compared to hole-in-the-ground toilets and tent camping on the Mongol Rally, staying in a capsule hotel was pure luxury. Unfortunately, although capsule hotels market themselves as “budget” accommodation, it didn’t come cheap. At £40 per night for two capsules in the heart of Shinjuku, the price wasn’t bad by Tokyo standards, but it was pretty expensive to us. After our one night of relative luxury, we checked out of our capsules and went back to roughing it at a seriously budget guest house down the road for half the price.

One floor of our capsule hotel

A typical capsule

- Meeting Asimo the robot

After the robot-restaurant-fail, my next attempt to visit Tokyo’s robots took place at the Emerging Science and Innovation Museum. The museum was packed with interesting exhibits about new technology, from using the human body itself as an electronic communication device to 3D printing in every home. We went to see a replica of the international space station, read about how Japan is trying to use technology to improve levels of physical activity using different types of music technology and saw the museum’s star attraction: Asimo.

Shane and I had both seen Asimo on TV, so seeing him in real life was a little bit like meeting a celebrity. Asimo is a humanoid robot, so he has a human shape with arms, legs and a face, and moves and talks a bit like a human. We watched Asimo walk, talk, kick a football and sing a song complete with Japanese sign language. It was very impressive, and went some way towards making up for the disappointment of not seeing robots at the robot restaurant.

Asimo

- Disneyland and Disneysea

What could be better than visiting the happiest place on earth? Visiting the happiest place on earth with Shane, my parents and my brother, of course!

Mum, Dad and Tom flew out to meet us in Tokyo for a few days of Disney fun 🙂 Unlike the recent Disney park additions of Shanghai and, to a lesser extent, Hong Kong, Tokyo Disneyland has been around for 35 years. It contains all the Disney atmosphere and the classic rides, but is incredibly efficient, friendly and full of people who know how to dress in Disneyland.

While Tokyo Disneyland was very similar to the California/Florida/Hong Kong/Paris parks we know and love, Disneysea was an entirely new theme park with some incredible theming and new and exciting rides. One minute we were in Ariel’s mermaid lagoon, the next we were in a gondola in Venice. In Tokyo’s Disneysea we even spotted our old friend Lewis Hamilton, proving that when he’s not racing around, even Lewis can’t resist a bit of Disney time 🙂 No visit to Tokyo can be complete without a magical day out at Disney!

Tokyo Disneyland

Tom in his favourite Disney outfit

—

It’s been a strange and surprising week in Tokyo, and Mum, Dad and Tom are loving it just as much as we are. We will all be travelling together for the next two weeks, and thanks to them Shane and I are having a two-week break from dodgy hostels and airport sleeping. Tomorrow we are all leaving Tokyo on a cruise ship to see some more of Japan and some more of South Korea before we end up in Shanghai and have to go our separate ways again. Sayonara Tokyo!

Streets of Tokyo

Night time in Tokyo