For anyone who is settling down to read another one of Georgia’s well-written and accurate descriptions of our journey, I’m sorry. This time it’s my turn to write the blog. I don’t have a degree in English but hopefully with a little effort from me and a little editing from Georgia, you’ll be able to read this.

The last chapter of our adventure was our trek to Machu Picchu. After this we had one final stop before we left Peru for Bolivia; a visit to Lake Titicaca. It is the largest lake in South America, and at 3,800 metres above sea level, it is the highest navigable lake in the world. It was believed to be where the sun originated and is also considered to be the birthplace of the Inca people. In the local language “titi” translates as “puma”, and viewed from above the lake does resemble the shape of a puma, although it is not known how the ancient Inca people could have realized the lake was that shape.

After spending one night in the nearby town of Puno on the edge of the lake, we woke up early to take a boat out to visit the lake and some of the islands. First we visited the floating islands; small islands not far from Puno made entirely from reed beds. The islands had a spongy feel because of the various layers of reeds, and if a boat passed nearby at speed, the whole island would rock. We visited a number of the houses on one of the islands and although the island, the houses, the mattresses, and pretty much everything was made from reeds, they still managed to have TVs and satellite dishes powered by solar panels, so could keep up to speed with the world cup.

We also watched some traditional weaving and crafts, went for a short trip on a traditional boat (made from reeds) and learnt about the local way of life. We also learnt about the continuous construction of the islands, which sounded exhausting. New reeds have to be added to the top of the islands constantly, and the islands can last about thirty years, after which a new island has to be constructed. While it seemed like a lot of effort just to maintain a place to live, there were some obvious advantages, such as being able to hide from Spanish invaders in the past, or these days just floating away if you fell out with your neighbours.

While interesting, the islands also had a very touristy feel, and it was difficult to get a sense of how much of the way of life we saw was ‘real’ and how much was a kind of performance for visitors. While tourism no doubt provides a valuable source of income for the people of the floating islands, it must also cause a fair amount of damage to these precarious places. Overall, while Georgia thought living on a floating reed island seemed like more hassle than it was worth, I think they could provide a nicer, cheaper alternative place to live than some of the unfinished redbrick apartments in the nearby town of Puno.

Floating reed island in Lake Titicaca

Taking a small, traditional reed boat around the islands

Learning about life on an island made of reeds

—

After the floating islands we continued on our boat trip to the island of Amantani, where we were going to stay the night with a local family. Once we arrived on the island we were divided up between houses and introduced to our new “mothers” who would be looking after us for the next 24 hours.

Amantani was a natural island rather than a floating island made of reeds, with more substantial houses and infrastructure (though no cars), and plenty of space for tourists. Our room was basic but had lights, and lots of blankets for the cold night at altitude. The food was largely potato-based (in fact one meal consisted of five different potatoes, one of which looked like a grub) and was tasty with lots of coca, mint or wild lemon tea to wash it down. Coca tea is drunk a lot in Peru, but as it’s a source of cocaine it is illegal in many other countries and just one cup of tea could cause you to fail a drug test.

In the evening we climbed to a temple at the highest point of the island where we watched the sunset, and then got dressed up in some traditional clothes in the evening to participate in some local dancing.

The next morning, after breakfast, we returned to our boat and said goodbye to our temporary mothers. We then stopped at another nearby island and enjoyed a walking tour with stunning views, which finished in the main square of a small town. Once again we had an opportunity to buy various knitted and woven items, although on the island the men completed most of the knitting. Over lunch we learnt how the men court the women based on the quality of a hat they have to knit. The knit has to be so fine that the hat will hold water when filled.

Lake views

Watching the sunset from Amantani island

James, Shane, Georgia, Ryan, Holly, Will, Jess and Andrea

Climbing up to see the view

Georgia ready for the cold

Andrea, Holly, Jess and Georgia in their traditional clothes

Great views of the milky way

—

Once we’d completed our island tour and said goodbye to Puno, we continued to drive along the banks of Lake Titicaca passing trout fisheries and small villages until we reached the border with Bolivia.

Apart from a tourist bus, which crossed before us, the border was completely deserted. The buildings were brand new, and it looked ready to deal with ten buses at a time, but apart from us there was no one else. It was a relatively quick and straightforward crossing, and then we continued straight to the sprawling city of La Paz, described by Jeremy Clarkson when he visited as “horrible, dirty and too high up.”

The city is on two levels and moving between them is like driving off the side of the cliff. The city centre is at 3,650 metres above sea level, while the second part of the city (El Alto, meaning “high”) is at 4,150 metres. To get between the levels you can either take a taxi or bus down steep, twisty roads with many switchbacks, or get one of the public cable cars, which are very modern and good value at around 30p per ride.

Flattering view of La Paz from El Alto

Jeremy Clarkson and the Top Gear crew were in Bolivia to drive the Death Road, otherwise known as the The World’s Most Dangerous Road. We were also here to see the road but instead of driving we were going to cycle down it. The cycle would start at 4,700m surrounded by snow down to 1,100m into a tropical jungle. This is the main reason I am writing this blog, as Georgia did not feel her cycling skills were up to it. She did still travel down the road in a minibus, which might have been even scarier. On a bike you have to trust yourself, while in a bus, you have to trust the snacking, fidgeting, distracted driver.

The World’s Most Dangerous Road is a narrow, rough track on the edge of a mountain, which used to be the only road joining La Paz to the north of Bolivia. Lots of trucks, buses and cars have collided and / or plunged over the edge, and around 300 people used to die either on or falling off the road each year. While normal driving in Bolivia (as elsewhere in South America) is on the right, on this one particular very dangerous stretch of road, the rules switch and driving is on the left. This is to allow the driver to lean out of the window to see where the edge of the road is when meeting other traffic, but adds an extra ounce of confusion to an already dangerous road.

In recent years the traffic on the road has dramatically reduced. The government have built a new road which now handles the traffic going to and from La Paz, leaving the “death road” quieter for crazy tourists like me.

—

On the morning of the cycle we drove one hour from La Paz, put on all our gear, (jackets, gloves, helmets and optional knee and elbow protection), tried our dual suspension bikes out for size and had a quick pedal around a car park. Once we were all ready, with go-pros in place and saddle-heights adjusted, we formed a circle and listened to instructions from our guide. The main rule: “don’t be an idiot”. Cycling the death road is not straightforward and carries certain obvious risks. While bikes are much narrower than trucks, there is still a 400+ metre drop and the road conditions and surface are still poor. There have been around 30 recorded deaths from cycling over the last few years, which is a lot, but also a lot less than the numbers who die on the roads in the U.K. every year.

We were given our rules, promised not to do anything stupid, and were then given 96% alcohol to drink. Yes, that’s right, we were about to cycle down the “Death Road”, but here we were drinking alcohol.

In fact the alcohol is not meant to be used for getting drunk; it’s a ritual, which is done to appeal to the ancient gods and ensure our safe return after the cycling. We had to pour a little on our bikes, a little on the ground and have a sip. I hoped that good bikes and common sense would get us down safely, but there was no harm in a little extra help.

The first section of our cycle was a tarmac road. It was all downhill, and so we went very fast, as fast as the bikes could go. The only things that slowed us down were the wind and a little bit of fear.

There were some bends, which I did have to slow down for, as well as bumps in the tar, trucks to pass, sections in the shade and some in bright morning sunlight. We had regular stops to regroup on the way down. All was going well, and we stopped for photos at a viewpoint. This was the first time we really became aware of what we were about to do, as even at this viewpoint there were about 8-10 crosses, and we had not even reached the death road yet.

Warm-up cycling on the tarmac

After this point we had some more fast downhill sections, and it was on one of these that the first accident of the day occurred. Will’s bike started to wobble, the front wheel snapped sideways, Will went over the handlebars and slid for about 40 metres. Thankfully there was no drop off the edge here. Traffic behind started backing up, and Andrea had to make an emergency stop and also went over the handlebars. Once the traffic moved off it became obvious that Will was hurt. Andrea was bruised, but was able to continue riding, while both Will and his bike were clearly injured.

After some discussion it was decided that Will should go to hospital and an ambulance arrived to transport him back to La Paz. There were mixed emotions in the group as some were worried about continuing, and everyone was worried about Will. It was a huge shock, and it slowed the pace down before the next section: the start of the Death Road.

—

As we arrived at the start, we saw a twisty, wet, rocky path snaking alongside a cliff. The road was shrouded in cloud, and while we could see a sheer drop, the view was obscured with mist, which gave the place an even more ominous feel. “If you go over the edge”, the guide warned, “we do have ropes, but they are only 100 metres long”. Not much use if you fall 400 metres down. We geared up again, our bikes were checked over to ensure they were all working correctly and set off into the mist down the mountain. The speed was good and as I do like mountain biking I really enjoyed it, and it wasn’t long before we were passing other groups.

Ready for the Death Road

At the same time we still had to be careful. Right hand bends were tricky because if you came off or couldn’t make the turn you would go over into the abyss. On left hand bends there was a risk of hitting the cliff wall or an oncoming car or motorbike. Thankfully, during our full day of cycling we were lucky enough not to meet a truck.

We had a few more slips and slides from the group on the way down and another bike out of action, but in the end we all made it down safely. The ride finished at a rescue centre for wild animals where we had a tasty meal and watched the photos from our day’s exploits. Apart from some sore arms (from the continuous vibrations) sore bums and a few bruises we all made it back in a good mood.

On the edge

Speeding along

A particularly nasty spot where others have perished

So now you may be wondering, what about Will? Later in the evening a few of us went to the hospital to bring him some clothes and items. He had a broken his collar bone and would require surgery to have a plate fitted. This was scheulaed to happen the following day and he was in good spirits. At the time of writing is back with the group but will have to stay in a sling for a number of weeks.

—

While Death Road was the highlight of La Paz, we also spent some time exploring the city. We went on a walking tour where we saw the prison made famous by the book Marching Powder, learnt that it was once the producer of the finest cocaine anywhere in the world and, importantly, were told that we shouldn’t take a tour of the prison (these are not officially offered any more, and recently some tourists ended up locked in until they agreed to pay prison guards a few hundred dollars to let them go). We also visited the witches market, which had a number of dead llamas and llama fetuses as offerings to the gods. We learnt that when someone wants to build a house they bury a llama in the foundations to protect the house in the future. When someone wants to build a bigger building (such as a large hotel maybe), they bury a human alive as an offering. Hopefully this is just an urban legend, but apparently there have been human bones discovered in the foundations of many large, old buildings…

Llama fetuses at the witches market

We also enjoyed a trip on the famous cable car, visiting the El Alto area of La Paz for a view. Trying to get on an escalator to the cable car proved to be an interesting experience, as crowds of people gathered at the entrance to the escalator, seemingly unsure of what to do or where to go. While at first this was a little frustrating, we then realized that it was because many of the local residents had never seen or used an escalator before! On our last evening in La Paz we went out to a delicious steak restaurant for a group dinner, as we were saying goodbye to Hattie. After two weeks of struggling on through illness, Hattie was going to rest and recover at home.

Views from the cable car

The hanging mannequin acts as a warning: this is a “neighbourhood watch” area of La Paz where the police will not visit. The residents police it themselves and this is what they will do to you if you commit a crime!

—

The next day we left La Paz and drove to the famous Uyuni salt flats, where the land is flat and white from salt as far as the eye can see. We headed onto the salt flats early in the morning in two 4x4s. The salt was very smooth to drive on and it wasn’t long that people were drifting off to sleep in the cars! Our first main stop was the cactus island, near the centre of the salt flats. This was an island in the middle of the sea of white, which was covered in cacti, some of which were 900 years old. We climbed to the top of the island for a magnificent view. 10,000 kilometers of salt stretched all around us.

Cactus island in the middle of the salt flats

After this we had time to use the expanse of salt to play with perspective and take some obligatory tick photos, then visit a hotel made of salt. The trip finished at a train graveyard where many of the steam trains, which were used in Bolivia, have just been parked up and left to rust at the edge of the salt flats.

Looking salty

Shane, James, Georgia, Andrea, Marisa and Holly recreating the stages of evolution

The dinosaur is coming, everyone is terrified

Squishing the rest of the group

Cute

Flags of the world

Dakar monument

Trains stuck in the ground at the train graveyard

—

From the salt flats we went to laugh in the face of danger again, as we visited the most dangerous mountain in the world. You may have thought that the most dangerous mountain in the world was Mount Everest, or maybe K2, but in fact it is Potosi in south Bolivia, and not from people climbing it but from people going inside it. This mountain, which towers above the city has been mined for five hundred years, and it is said that enough silver was removed from the mountain by the Spanish that a bridge could be built from Potosi all the way to Spain. Over the years it is believed that nine million people have died inside the mountain. The mountain is shrinking every year due to cave-ins, and the government have stopped mining operations due to safety concerns, but mining still continues today. After a lot of thought, discussion and investigation as to the safety of the mine (there is a lot of toxic gas in the air, and a risk of a cave-in is real), we decided to do a tour of the mines.

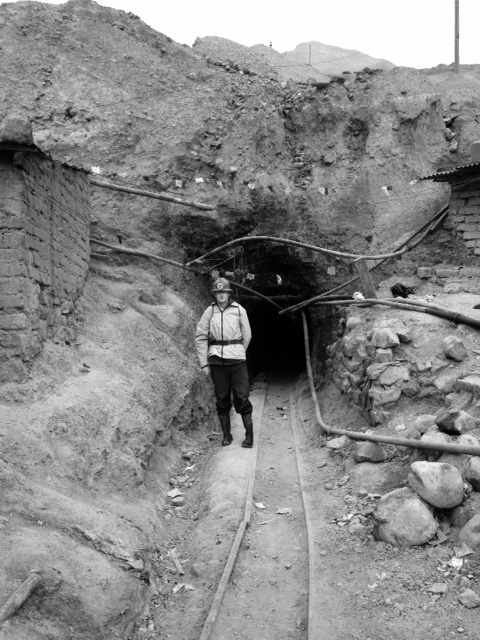

The tour started with us getting suited up in waterproof overalls, helmets and torches. We then headed to the miner’s market and a small shop where we could buy coca leaves, alcohol, and dynamite, and get some gifts for the miners we would be meeting. As it was Friday, it was suggested that we buy them a bag of coca leaves, a bottle of 96% alcohol and some fizzy orange to mix it with, as many drink early on a Friday to celebrate the end of the week. A stick of dynamite could also be bought for 20 bolivianos (about 6$).

Stick of dyanmite

Not far from the entrance to the mine, there was a statue of El Pio or uncle. This is a human type figure with the head of the devil and a large manhood. He was decorated with brightly coloured flags and coca leaves. Here we learned the daily tradition of giving offerings to the gods, which included sipping alcohol and pouring some on the ground, as well as letting the statue smoke a cigarette.

After this was done (it didn’t fill us with anymore confidence going into the mine!) we started to progress deeper into the mountain. We didn’t have to go far before we saw broken supporting timbers and parts of the tunnel where the timber overhead had already buckled with the weight. In many of the tunnels you were unable to stand up straight, had to splash through puddles and crouch down. After a while we were introduced to some miners who stopped working to sit with us and tell us about the mine and how long they have worked there.

Going in

We then headed deeper into the mine and had to move to a lower level, climbing down ladders or using rocks. Will had joined us for the tour and although many of these maneuvers were tricky for someone with two working arms he managed quite well just one. From here we went to where miners were working, covered in dust from head to toe. As we climbed further in, we started to feel and hear the first explosions. The whole tunnel began to shake, and the blasts continued. The guide said the explosions were happening around 100 metres above our head, but they create so much dust that work in the mines can’t continue for a number of hours.

Crouching

Meeting the workers

After more moving from tunnel to tunnel we were (to some people’s relief) told to follow a set of tracks, which would lead us out into daylight. After walking for nearly a kilometer through the darkness and crouching in tight spaces we eventually saw daylight. After nearly two hours underground it was nice to be able to breath the fresh air and not dust! For the people who live down the mine this must be a great relief after up to 14 hours of working in the mines.

We left the mine and headed back to the town where we got to remove all our protective clothing and become normal tourists again.

That night, as I hadn’t seen Georgia for the day, we decided to go out for dinner and found a really nice restraint which was named after the height of the town and planned our visit to some of the sights of the city the next morning. We had time to visit the city’s mint in which millions of coins were forged and sent all over South America. The tour was interesting and much of the building and equipment remained intact. Rather than replace the existing equipment they seemed to just install the new equipment in a different area. It also helped that as they progressed from mule-powered production to steam-powered production to electricity-powered production the size of the equipment also reduced.

Views of Potosi

The mint

On leaving Potosi we headed towards the Argentinian border and had one bush camp along the road on a dry riverbed with some bulls which looked on with intrigue as we put up our tents.

We left Bolivia after only one short week, but our time was packed with adrenaline, history and salt. Despite the fact that the Lonely Planet describes Bolivia as “a country that should never have existed”, and La Paz as a “gritty city of diesel, dust and detritus which amazes and appalls all who enter”, we had some very memorable experiences of a different kind. At the same time, we couldn’t help but look forward to steak, wine and a calmer time in Argentina. Thank you Bolivia, for letting us avoid death and allowing us to pass through safely.

One thought on “Cheating death in Bolivia”