Cuba. An interesting combination of perfect sandy beaches, cheap rum and lively salsa, with austere ration stores, bureaucratic processes and a flavor of totalitarianism. “Imagine a poorer version of Russia, with nothing in the supermarkets, two currencies and on a Caribbean island with lots of salsa and music”, is how I described the country to some of my friends. Cuba was a total paradox and completely unique. It was interesting, thought provoking and unbelievably frustrating all at once.

—

The difficulties started well before we landed on Cuban soil.

To save money, Shane and I had the genius idea to use our American Airlines airmiles to fly from Rio to Havana. We found a very convenient flight with just one short stopover in Miami, and apart from the negligible cost of taxes and charges, it was free.

Unfortunately, the United States government does not permit people to travel from the USA to Cuba for tourism purposes, and this applies to everyone – not just American citizens. To travel to Cuba, the purpose of our visit had to fit within one of 12 categories, such as visiting family, official business of the U.S. government, or humanitarian projects. We chose “educational activities”, and then booked a cheap tour with local company Cuban Adventures, which promised to satisfy the U.S. regulations and involve some sort of educational experience. If anyone questioned our reasons for travel, we could produce our itinerary.

To make matters worse, as we were not travelling to Cuba for tourism purposes, we couldn’t buy the normal tourist card (which usually costs about £20 from the Cuban embassy in London). Instead, we had to buy a special American Airlines approved visa, which was pink instead of green, cost $100 each, and still said “tourist card” on it, even though we were (officially) not tourists. Having purchased our Cuban Adventures tour and our pricey visas, suddenly our “free” flights no longer seemed like such a good deal.

—

On the plus side, the process of flying to Cuba was fairly smooth. We checked in for our flight using a self-service kiosk, which asked us to declare our reasons for visiting Cuba, but asked no other questions. When we dropped our bags off, the check-in assistant seemed surprised that the machine had allowed us to check in for a flight to Cuba. “Did the machine ask you questions, like why you’re going to Cuba, what you’ll be doing there, and where you’ll be staying?” he asked, looking perplexed. We tried to dodge the question, as it had only really asked us one of those things, and repeated several times that it had asked us about “the purpose of our visit to Cuba”. He eventually seemed satisfied, if a little surprised, and checked in our bags. Somehow we had escaped through the net with minimal questioning, and were on our way to Cuba.

We arrived at Havana airport – a utilitarian building, described by one internet commentator as “a kind of warehouse” – and were actually pleasantly surprised. Immigration was fast, and although our bags were not, it appeared nothing had been stolen from them, which is always a plus. We didn’t have to stop at customs, and quickly found ourselves in the arrivals hall.

My Cuba-related research had led me to believe that accessing cash in the country might be a problem. Tidbits of information I read included “nowhere takes credit cards in Cuba”, “ATMs frequently don’t work in Cuba”, “ATMs won’t accept mastercard in Cuba” (our only international fee-free ATM card is a mastercard), “YOU NEED TO BRING ALL THE CASH WITH YOU IN CUBA”, and “There is a 10% tax when you exchange US dollars, but not when you exchange pounds or euros in Cuba”. While my Halifax Clarity credit card has been unbelievably reliable, working in every single country on pretty much every single occasion around the world over the last 14 months, I didn’t want to rely on it completely, and so it was that I ended up carrying around £500 GBP for the last four months, specifically for the purpose of our trip to Cuba.

This turned out to be for nothing, as I went straight to the ATM at the airport, found that because the banks (along with everything else) are owned by the government, there are no extra charges for withdrawing cash at the airport (thank you socialism), and withdrew plenty of money on the first try. Getting a taxi to Havana was also simple. The price was set by the government at about one Cuban convertible peso (equivalent to one US dollar) per kilometre, so it was refreshing not to have to haggle, or to worry about being ripped off.

—

Driving into Old Havana was like travelling back in time. The city was beautiful if a little crumbly, the roads were virtually empty, and where we did see cars, they were beautiful, old classics. We stayed in a “casa particular” – a private house run by a local family, like a B&B or guesthouse rather than a government-run hotel – and started to explore the city.

Pretty Havana streets

Classic cars

We visited the Museum of the Revolution, which turned out to be half empty, and half full of communist propaganda, recounting endless attempts by the CIA to destroy Cuba. We also wandered the streets, visited Ernest Hemingway’s old haunts, and had our first taste of Cuban music. We were quickly taken in by the charm and beauty of old Havana.

Museum of the Revolution

But it wasn’t long before we started to encounter the trials and tribulations which plauge Cuban people in their daily lives. Cuba’s socialist system is successful in many ways. Free and good quality healthcare and education combined with subsidised housing, utilities, entertainment and food programmes have led to successful social outcomes. Life expectancy and literacy are higher in Cuba than in the USA, while levels of homelessness, inequality and crime are much lower. At the same time, Cuba is a one-party state, and the government controls all aspects of people’s daily lives. No political parties are allowed to exist (except the Cuban Communist Party), and criticising the government is a serious offence.

Our first challenge was to try and communicate with the outside world. We wanted some access to wifi, so we could tell our families we were still alive, and access information about the places we would be staying and things to do. Getting access to wifi, and other forms of communication (like public phones) is a convoluted process, which, like everything else, is controlled and administered by the Cuban government.

Our attempt to get on the internet went something like this:

Step 1: Find an ETECSA centre (a communications centre run by the government where you can buy a special card to access wifi, a different special card to access pay phones, use a computer, or do various other communications related things. We found there was usually one in each town.)

Step 2: Find out that the ETECSA centre has closed early / wifi cards are unavailable / there is some problem.

Step 3: Return to the ETECSA centre at another time and hope that the problem has been solved.

Step 4: Wait in a long, disorderly queue outside the building for about an hour.

Step 5: Eventually get to the front of the outside queue, go inside the building and join another long, disorderly queue with no clear system in place for about half an hour. Notice that there are about ten members of staff hanging around, but only one or two are actually doing anything useful. The rest are chatting, looking at the floor, shuffling papers around or just waiting for the day to end.

Step 6: Eventually make it to the front of the inside queue (whatever “the front” is, when there is no real queue) and go to see the one member of staff that seems to be doing something.

Step 7: Ask to buy a wifi card, hand over passports, and wait another fifteen minutes while nothing happens.

Step 8: “Computer says no”. For some unknown reason, there is a problem, and wifi cards cannot be purchased at this time.

Step 9: Wait.

Step 10: Wait a bit longer.

Step 11: See a different person and try to buy a wifi card. Have the following conversation in a mixture of Spanish and English (but mostly Spanish):

Georgia: “I would like to buy a wifi card please.”

ETECSA employee: “Would you like a five-hour card or a one-hour card?”

Georgia: “I would like two five-hour cards please” (so I never have to do this again)

ETECSA employee: “We only have one-hour cards.”

Georgia: “OK, I’ll buy ten one-hour cards.”

ETECSA employee: “You can only buy three.”

Georgia: “OK, I’ll buy three”.

Step 12: Handover passport and three Cuban convertible pesos (equivalent to US$3), and buy three hours’ worth of wifi.

Step 13: Leave the ETECSA centre, thinking about the hours spent in the endless queue that I’ll never get back, and vowing to be less dependent on the internet from now on.

Step 14: Look for a place where I can actually use the wifi card and access the internet. This could be done outside most ETECSA centres (though, conveniently, not the one in Old Havana), in some public squares, and occasionally at hotels.

Step 15: Log in and discover that the wifi is really slow or doesn’t work at all.

Step 16: Log in again and discover that somehow the card doesn’t work properly and all the wifi I bought has now disappeared.

In the “queue” for wifi

—

In Havana, we also met with the rest of our Cuban Adventures group (Sarah from New Zealand, another Sarah from Malta, and Jane from Australia), and travelled to Havana’s domestic airport to fly to the town of Baracoa at the eastern tip of the island.

‘Airport’ turned out to be a generous term for the small building where we waited to board a tiny plane, complete with propellers and plenty of people who had never been in an aeroplane before. The “safety demonstration” consisted of nothing more than advice to “look at the safety card in the pocket of the seat in front of you.” I always like to pay attention to the safety demonstration on a plane – just in case – so duly reached into the pocket of the seat in front of me. I found nothing whatsoever. “Nice try”, said a German tourist sitting next to me, and from the rapturous applause that erupted when the plane touched down in Baracoa, it seemed that I wasn’t the only one who had felt a little nervous about the plane’s safety standards.

The “airport”

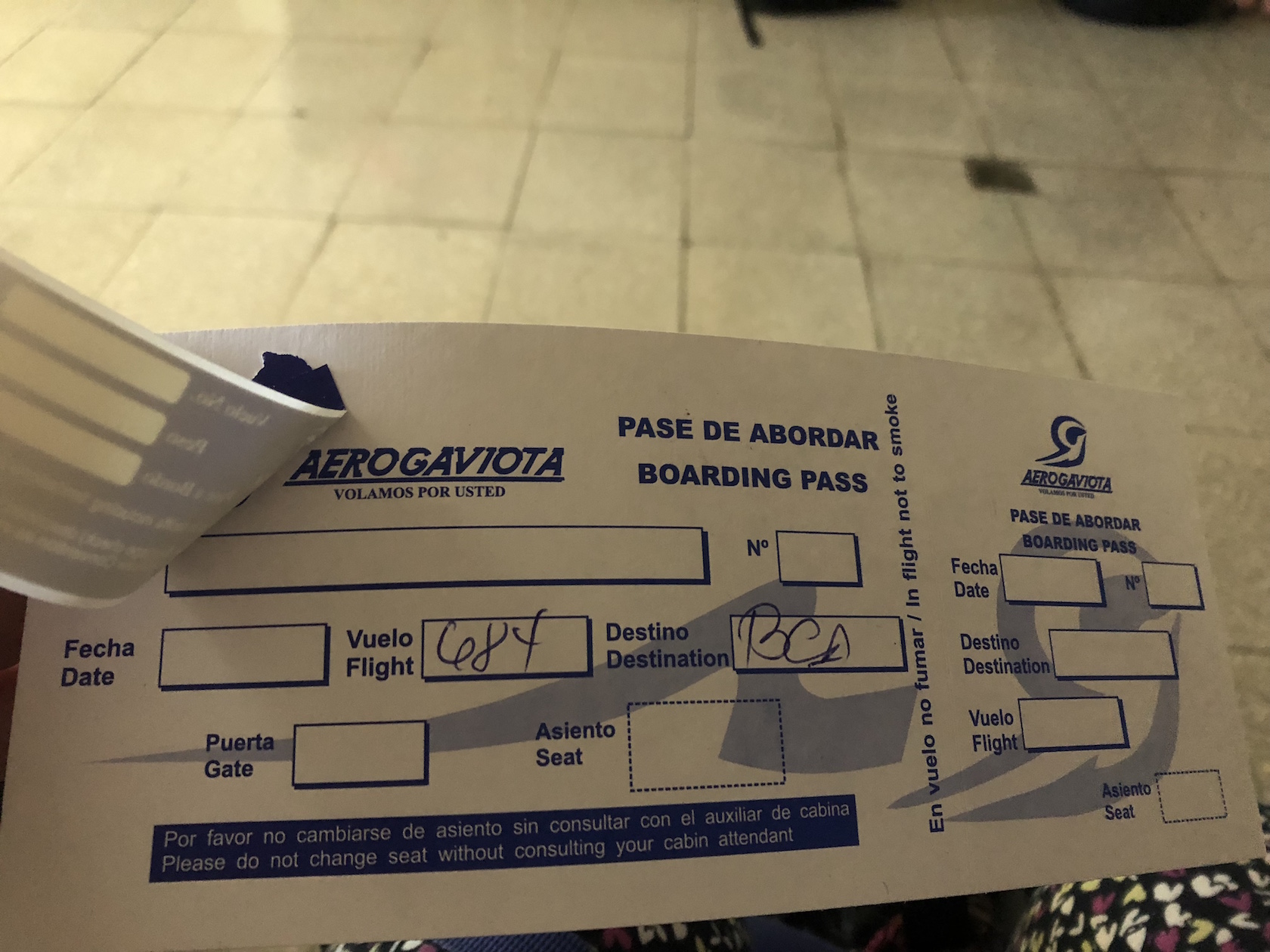

Detailed boarding pass

Busy day at the airport

Baracoa was a small, peaceful town, surrounded by luscious jungle and a pretty beach. While Shane ventured out exploring the nearby gorge, a local fishing village and a chocolate plantation, I had developed some kind of stomach bug, so stayed at home trying to recover. When recovery stalled, I ventured out to the local pharmacy, and had an interesting time trying to buy some medicine.

The pharmacy looked like it was 100 years old, and there was barely anything on the shelves. I used my best Spanish (combined with a little help from google translate) to explain that I wanted medication for diarrhea that did not contain penicillin. The pharamacist produced a small bottle of something that looked suspiciously herbal and probably ineffective. I politely asked if she had anything else, and she found some tablets. I had no idea what they were, but she assured me that there was no penicillin in them, and that they would do the job. I said I would take them.

The problems started when I tried to pay. There are, in fact, two currencies in use in Cuba. The cuban convertible peso (CUC) is designed to be used by tourists, and its value is pegged to the US dollar. One cuban convertible peso = one US dollar.

When I asked how much the antibiotics were, the pharmacist told me they were 1.50. I assumed this meant $1.50 CUC, and duly handed over the money. $1.50 seemed like quite a good deal, considering that the prices we had been paying for food in restaurants, or water in minimarkets (where we could find it) were quite high.

Unfortunately, the pharmacist was not happy with my offer of $1.50. It wasn’t until she said “moneda nacional” that I understood the problem. The price – 1.50 – wasn’t 1.50 CUC. It was 1.50 Cuban pesos (of course, Cuba has two currencies, and both are called “pesos”). Cuban pesos, or moneda nacional, is Cuba’s other currency. Most people are paid their salary in Cuban pesos (CUP), most local shops only accept CUP, and apparently, this pharmacy would only take payment in CUP. The good news was that the cuban peso has a much lower value than the cuban convertible peso – 1/25 in fact – so instead of costing $1.50, my antibiotics cost $0.06. Bargain. The bad news was that I didn’t have any CUP.

What followed was a long and difficult discussion, which ended in me giving the pharmacist CUC $0.10, and her being sort-of-happy-but-not-really. When I got home, I googled the tablets she had given me, and found out they were really for treating amoebic dysentery rather than traveller’s diarrhea. I took them anyway.

—

Feeling a little better the next day, I joined Shane and the others for a walk through the jungle to a waterfall. This involved crossing rivers, spotting hummingbirds, swimming in the waterfall and a nearby river, eating delicious fruit, and generally soaking up the relaxed atmosphere of Baracoa’s surroundings.

Green Baracoa

Who needs a bridge?

Crystal clear water for swimming

But the relaxed atmosphere evaporated when we reached our next destination Santiago de Cuba (with a quick stop at Guantanamo Bay on the way). Cuba’s second largest city is known for its role in the Cuban revolution, and so we set about exploring the Moncada barracks where Fidel Castro launched an attack in 1953, and Santa Ifigenia Cemetry, where Fidel Castro and Jose Marti are buried.

As we approached the Santa Ifigenia Cemetry, we were stopped in our tracks by four or five people in police uniform. While they weren’t unfriendly, they were very clear about where we could and couldn’t stand, and the route we needed to take to get into the cemetry. As we followed the route, we encountered more and more police, who seemed to have nothing to do other than direct people along the path. “Wouldn’t a sign have been cheaper?”, I pondered, as we made our way into the cemetry.

Once we were finally inside, we were stopped again. This time by a woman with a special badge:

“Where are you going?” she asked irritably.

“We’ve come to the cemetry”, we explained, in case that wasn’t clear. “We’re going to see the graves.”

“Well you can’t be here without a ticket. You need to pay.”

“OK, where can we pay?” we asked, as we had carefully followed the directions of about thirty policemen and women to get into the cemetry, and hadn’t seen anywhere that it might be possible to buy a ticket.

“The only ones you can see if you don’t pay are those ones”, she replied, pointing us towards the grave of Jose Marti, the main feature in the middle of the cemetry.

We decided to just visit the graves of Jose Marti, Fidel Castro, and the mother and the father of the nation, as there was nowhere to pay, and apparently no way we were allowed into the rest of the cemetry.

Fidel Castro’s memorial

The off-limits cemetry

Our experience at the Moncada Barracks wasn’t much better. We bought a ticket, roamed around the museum, and then tried to explore outside. Suddenly, members of staff seemed to appear from nowhere, telling us “no”, that despite buying a ticket, we would not be allowed to wander freely, and cajoled us back into the building..

—

Our next stop was Camaguey, another pretty city with old buildings, cobbled streets and pretty churches. The city was built with a deliberately confusing layout. There are plenty of blind alleys, squares of different sizes and streets that look the same, apparently to stop pirates from finding their way around. If this is true, it definitely worked – we spent two days struggling to navigate – and even Shane managed to get lost.

We started our day in Camaguey with a bicycle taxi tour, which was included with our Cuban Adventures trip and was very informative. We stopped at a number of churches and some interesting art galleries, and learnt about the history of Cuba and Camaguey. We then visited a couple of historic houses, which again contained twenty or thirty members of staff who didn’t seem to have a lot to do, and tried to have dinner in the evening. It was at this point that we came unstuck again.

The first cafe we tried claimed to have no water, no cola, no juice, and no wine, despite serving Cuba Libres (rum and coke), and glasses of wine to the table next to us. We then ordered chips and fried plantain as a snack, and again, despite the table next to us receiving massive portions of the same, we were given tiny plates and then told they had run out. It’s hard to know whether they genuinely had run out of everything (as they have little control over what deliveries they receive from the government), or were just being difficult.

We tried another restaurant, and found the same. They claimed not to have anything on the menu (although we could see other people eating the very things we had asked for), but were also unnecessarily rude. We wondered whether we had done something wrong by trying to eat in ‘local’ restaurants rather than ‘toursit’ restaurants – and so were taking resources away from local people unnecessarily – and decided to try somewhere else so as not to upset anyone. The difficulty of getting food – either in a restaurant or even in a minimarket – was a common problem during our time in Cuba. Bottled water was particularly scarce, and we never saw snacks like crisps or chocolate. One day I saw some cans of diet pepsi in a corner shop, and was so excited that I bought five.

At the same time, we were often successful in our search for ice cream – one of the staples of Shane’s diet – and on one particular occasion on the way to Trinidad, we found a local ice cream parlour. A government-run ice cream parlour seems strange in itself, but what was even stranger was the amount of ice cream people seemed to be eating. The couple next to us had three bowls of ice cream each, plus a huge slice of cake. When Sarah pointed at their table and asked for “what they’re having”, she didn’t expect to get the same quantity, but that’s exactly what happened. While Sarah did well, Shane was an ice cream champion. One huge slice of cake and four bowls of ice cream later, we waited nervously for the bill. At four cuban pesos ($0.15), it wasn’t exactly outrageous, and so I left the ice cream parlour with one happy Shane, and one slightly queasy Sarah.

—

Our next stop, Trinidad, was a definite highlight of our trip to Cuba. We encountered musicians playing in the streets, found people dancing salsa, ate some good food and took a very interesting walking tour around the city. The walking tour was a “free” (tips-based) walking tour, which we learned technically wasn’t allowed to operate in Cuba. Our tour guide explained that while education and housing are free, and food, rent and utilities are subsidised, the government wage of $20-$40 per month doesn’t go far enough for Cuban people. If they want to buy anything classified as “non-essential”, they need far more money than the government pays, and so many Cubans have a second job, where they can earn cuban convertible pesos, and buy some “luxuries”.

Pretty Trinidad

While the government turns a blind eye to many of these second jobs, tacitly accepting the fact that government wages don’t go far enough, our tour guide explained that others who work in the (government run) tourist industry didn’t appreciate him providing “free” tours, which enabled him to make a lot more money for a lot less effort. To stay out of trouble, he deliberately acted and dressed like a tourist – from the way he cut his hair to the way he spoke English! It was great to get his views on the negative side of living in Cuba, although I couldn’t help but feel that he had a slightly rose-tinted view of the rest of the world. “We’re 200 years behind everyone else”, he claimed, and while the buildings, cars and furniture are certainly older than in many other places, they are also rich in character. While Cuba’s system no doubt has its flaws, it seems that many Cubans are presented a very positive image of life in other places, which doesn’t match reality. Hollywood films and music videos show only the glamourous and wealthy side of living in a capitalist society like the United States. They don’t show the number of people living on the streets or being shot in schools. Most Cubans have never travelled outside of Cuba, and don’t have reliable access to information. While people in other parts of the world may have more freedom and in more opportunity, many are also poor, starving and homeless. Not everyone who lives in the USA lives like Beyonce, but the average Cuban only sees Beyonce, and (understandably) feels that they are missing out.

—

From Trinidad we made our way slowly back to Havana. We stopped in Santa Clara to visit Che Guevara’s grave and went snorkelling in the Bay of Pigs, where the CIA tried and failed to invade Cuba in 1961. Our last day in Old Havana was spent walking around the city one more time, appreciating the beautiful buildings and the old classic cars.

The Bay of Pigs

Our 17 days in Cuba gave us a good taste of the country, but I left feeling more confused than when we’d first arrived. How important is freedom? Is it more or less important than equality, health and wellbeing for all? What would Cuba be like if the United States embargo were lifted? What would Cuba be like if the CIA hadn’t tried to destroy it at every opportunity? Would I be happy in a socialist society, if it meant giving up my non-essentials? 17 days without chocolate, decent wifi or a proper supermarket suggests probably not. But what if I’d never got used to those non-essentials in the first place? Would the inefficiency and lack of productivity eat away at me? Are inefficiency and low productivity inevitable in a society where everyone is employed by the government on a low, fixed wage? Did we even experience the “real Cuba” anyway? Or did we just see the toursity side that the government wanted us to see?

There’s no doubt that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, life in Cuba was very hard for many people. But somehow Cuba has survived, with its regime more or less intact. How many other countries would be able to say the same, if they had been deliberately economically isolated by the largest economy in the world (which also happens to be one of its closest neighbours) for nearly 60 years? Yes, the buildings and cars are old, yes the regime has had to adapt and become more flexible with the introduction of toursim and limited private enterprise, and yes, the Cuban society is far from perfect, but what is amazing is that the people are still healthy, still safe, and still dancing.

I am glad we visited Cuba. It really is a beautiful country, with so much character, an interesting history and a very different way of life. It left us with a lot to think about, and it challenged both my patience, and, to an extent, my view of the world. It wasn’t all salsa, cocktails and beaches – at times it was frustrating and maddening – but it was an experience which I won’t forget any time soon. It also revealed that I was getting worn down by the trials and tribulations that come with travelling the world, and that I was nearly ready to go home.

It sounds as though Cuba is the ideal place for a philosophy graduate!

Sounds like you had a mixed time! We spent 8 days there just after you guys, its a very confusing place. It felt safe, very poor but not unhappy. We met lots of nice locals and I felt that life was simple. I am worried about tourism massively influencing and changing the culture, people and look of the country, not sure it can handle or is prepared for the American Market to open up fully. I was surprised how many tourists travelling in Cuba were American already! Its a beautiful place and I thoroughly enjoyed it.